Use Built-In XPath Functions

In developing one of the Altova Online Training courses, I sorted a list of books by the authors. I realized that my author field was a string of the author’s full name, so the books were sorted by the first letter of the string, or the author’s first name. It did not fit into the course to fix the sorting, but you can easily extract the last name from a string and use it for the sorting key using XPath functions. If you then use the books’ titles for a secondary sort key, you run into an issue with titles that start with “A”, “An”, or “The”. I want to use the title for the secondary sort key, but ignore a leading definite or indefinite article. Let’s take a look at how we created this XSLT code.

Let’s take a look at how we created this XSLT code.

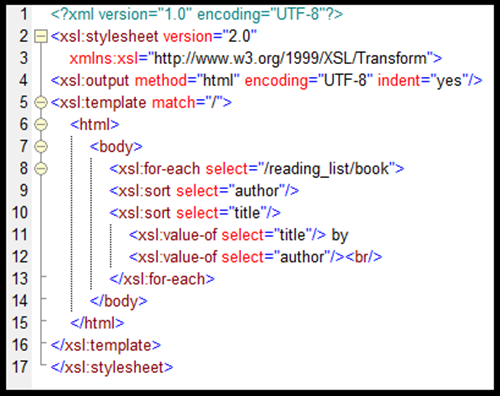

This article was written using XMLSpy as the platform, but the same XPath expressions can be used inside MapForce or StyleVision to achieve similar results. We can start with a simple XML book list. We have 4 books with author and title nodes.  An XSLT to create a list of the books would look like this:

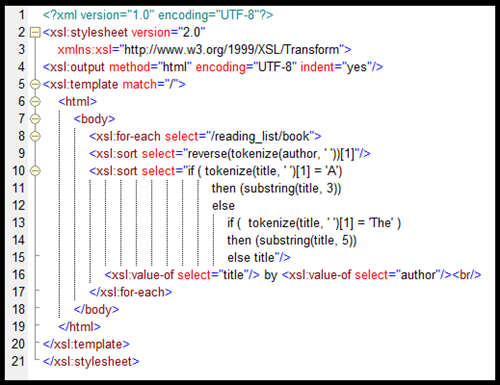

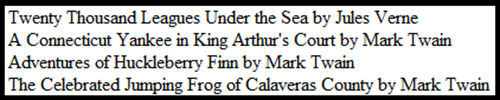

An XSLT to create a list of the books would look like this:  This will generate the following output:

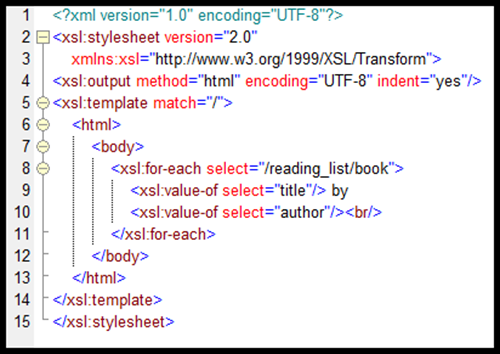

This will generate the following output:  The books are output in the order they appear in the original data file. If we add xsl:sort to the xsl:for-each loop, we can arrange our output in other ways.

The books are output in the order they appear in the original data file. If we add xsl:sort to the xsl:for-each loop, we can arrange our output in other ways.  This will generate a sorted list, but not sorted properly.

This will generate a sorted list, but not sorted properly.  Sorting author as a string, results in “Jules Verne” appearing ahead of “Mark Twain”. Also, “A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court” appears ahead of “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn”. We want to ignore the indefinite article, “A”, so that “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” appears ahead of “A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court”. We can use XPath expressions to extract the sorting keys we want.

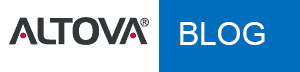

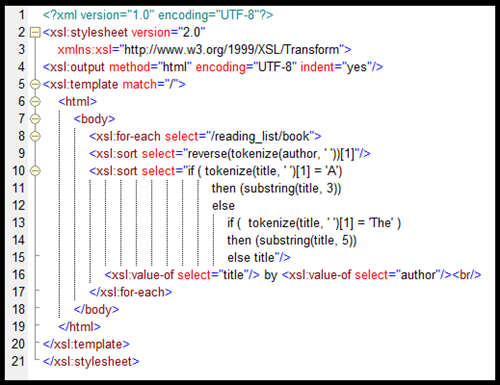

Sorting author as a string, results in “Jules Verne” appearing ahead of “Mark Twain”. Also, “A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court” appears ahead of “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn”. We want to ignore the indefinite article, “A”, so that “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” appears ahead of “A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court”. We can use XPath expressions to extract the sorting keys we want.  Let’s examine the code before we look at the output. We replace “author” with “reverse(tokenize(author, ‘ ‘))[1]”. Tokenize breaks the author string into tokens using a single white space as the break point. So, “Jules Verne” is tokenized into “Jules” and “Verne”. Reverse reverses the order of the tokens to “Verne” and “Jules”. The one in square brackets chooses the first item in the list, “Verne”. This is the value that is used in for the xsl:sort function to arrange the books. This is not the perfect solution, but it works in our case. The title looks convoluted, but the logic is straightforward. The “tokenize(title,’ ‘)[1]” expression extracts the first word of the title. So, the first if test is “Is the first word of the title the word “A”? “. If it is, then we return the substring of the title that starts with its third letter, thus eliminating “A” and the space. If the first word of the title is not “A”, then we need to test it again to see if the first word of the title is “The”. If it is, we use the substring of the title starting with its fifth character, thus eliminating “The” and a space. If we fail both tests, then we just pass the title along as the sorting key. We could add another test to our code to see if the first word is “An”, but it is not needed for this data set. Executing this last XSLT, we get the following output.

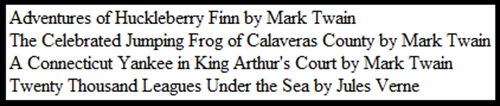

Let’s examine the code before we look at the output. We replace “author” with “reverse(tokenize(author, ‘ ‘))[1]”. Tokenize breaks the author string into tokens using a single white space as the break point. So, “Jules Verne” is tokenized into “Jules” and “Verne”. Reverse reverses the order of the tokens to “Verne” and “Jules”. The one in square brackets chooses the first item in the list, “Verne”. This is the value that is used in for the xsl:sort function to arrange the books. This is not the perfect solution, but it works in our case. The title looks convoluted, but the logic is straightforward. The “tokenize(title,’ ‘)[1]” expression extracts the first word of the title. So, the first if test is “Is the first word of the title the word “A”? “. If it is, then we return the substring of the title that starts with its third letter, thus eliminating “A” and the space. If the first word of the title is not “A”, then we need to test it again to see if the first word of the title is “The”. If it is, we use the substring of the title starting with its fifth character, thus eliminating “The” and a space. If we fail both tests, then we just pass the title along as the sorting key. We could add another test to our code to see if the first word is “An”, but it is not needed for this data set. Executing this last XSLT, we get the following output.  “Mark Twain” is now ahead of “Jules Verne”. “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” appears ahead of “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County” and “A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court”. The flaw in our approach to the author string is that we want “Jules Verne” to be treated as “Verne, Jules” for the sort, so that if we had a book by “Jimmy Verne”, the sort would treat them as different authors. Our code does not. Using “concat(reverse(tokenize(author, ‘ ‘))[1], reverse(tokenize(author, ‘ ‘))[2])” would sort “Jules Verne” and “Jimmy Verne” correctly, but this solution only will work with 2 word names. If an author had a suffix (“Martin Luther King, Jr.”) or multiple words (“George Herbert Walker Bush”), the code would fail. There are many exceptions to the general rules on alphabetizing names, and the code to allow for all variants goes far beyond the scope of this article. What we wanted to show was the ability to manipulate XML data on the fly using XPath expressions. We do not always have complete control on the format of our data sources, but using the power of XPath expressions, we can transform the data into the format that we need. A copy of the files used in these examples is available here.

“Mark Twain” is now ahead of “Jules Verne”. “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” appears ahead of “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County” and “A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court”. The flaw in our approach to the author string is that we want “Jules Verne” to be treated as “Verne, Jules” for the sort, so that if we had a book by “Jimmy Verne”, the sort would treat them as different authors. Our code does not. Using “concat(reverse(tokenize(author, ‘ ‘))[1], reverse(tokenize(author, ‘ ‘))[2])” would sort “Jules Verne” and “Jimmy Verne” correctly, but this solution only will work with 2 word names. If an author had a suffix (“Martin Luther King, Jr.”) or multiple words (“George Herbert Walker Bush”), the code would fail. There are many exceptions to the general rules on alphabetizing names, and the code to allow for all variants goes far beyond the scope of this article. What we wanted to show was the ability to manipulate XML data on the fly using XPath expressions. We do not always have complete control on the format of our data sources, but using the power of XPath expressions, we can transform the data into the format that we need. A copy of the files used in these examples is available here.